Moluccas, the fabled Spice Islands, and their fading culture

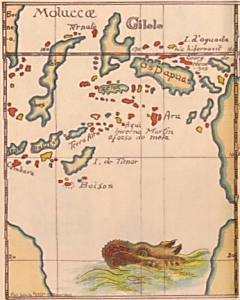

The Indonesian archipelago of the Moluccas (formerly called Molukken by the Dutch colonial regime, called Maluku in Bahasa Indonesia), traditionally known as the Spice Islands, straddles the equator North of Australia and West of New Guinea - 'Os Papuas'. It consists of hundreds of islands and islets. The name Maluku is thought to have been derived from the Arab trader's term for the region, Jazirat al-Muluk ('Land of Many Kings'). Until the 1700s, these mostly luxuriant, volcanic islands covered in rain forest were the only, or certainly the very best sources of such spices as cloves, nutmeg, and mace. The historical significance of the Moluccas cannot easily be overstated. It is largely because of the magnetic force of spices that European explorers - first the Portuguese, then the Dutch - risked sailing into unknown waters, which led to the discovery of the Americas, Australia, and of the routes along Cape of Good Hope and Cape Horn. There are few roads in the Moluccas, few ports large enough for modern ships, and even fewer airports. Except on the larger islands, most of the native settlements are situated on the coasts, and communication is principally by means of small, often barely seaworthy motorboats and traditional sailing prahus. Each of the major island groups has at least one town which is the focus of trade and the port-of-call for passenger carrying freighters. But most of these commercial centers are small and insignificant except as gateways for export and import. The only truly urban community in the whole of the Moluccas is Amboina, in the Ambon Islands south of Seram. Ternate, on an island of the same name, Tidore, just south of Ternate on another small island, and Bandaneira on the Banda Islands, in colonial days used to be flourishing trade centers, but their importance has declined greatly since the golden days of the spice trade. In the South Moluccas, the climate is too dry for the cultivation of spices, and in the past there were no mineral resources, which is why the colonial masters left this area more or less to its own resources. Gold and other minerals are now being discovered in the South Moluccas, which is likely to bring dramatic change to the area. On tiny Wetar for instance, there is already a gold mine in operation, which brings devastation of the natural surroundings and much pollution, while leaving most of the population as poor as before. This appears to be the inescapable fate of people in very poor areas all over the world where large corporations discover something to be looted. Ikat textiles - from the basic to the refinedExcept for Seram (formerly called Ceram), ikat is made only in the South Moluccas. The ikat textiles produced here range from the splendid cloths of Kisar, rich in imagery and with a striking tonality, to the artistically less ambitious but often surprisingly refined cloths of Tanimbar. While certainly important, culturally and sociologically they are not as vital to the communities as they are on Borneo, the islands of Nusa Tenggara (such as Bali, Flores, Lembata) and Sulawesi. Older cloths from the Moluccas are rare, and seldom found outside museums and the larger private collections. The largest collection of ikat textiles from the South Moluccas is in the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum in Cologne. Seram ikat, usually made of plant fiber other than cotton, is extremely rare, and found chiefly in old Dutch collections such as those of Tropenmuseum and Rijksmuseum Volkenkunde.Because the South Moluccas are lying on old trade routes, textiles from other islands have landed here since time immemorial and still show their influence. While the islands all have their own, easily identified style, motifs from Flores, Timor, and other islands do occasionally show up, albeit integrated in the traditional local design. One of our Babar cloths for instance has little horse motifs that were drawn exactly as in the Ende region of Flores, with a raised dock, almost certainly in imitation of an admired sarong that drifted over to Babar. Ikat textile is still being made in the Moluccas, especially on Kisar, but nearly all new cloths are made with chemical dyes only, appearing rather shrill in comparison with the warmer toned older ikat textiles from the island. A map of the South Moluccas, at the bottom of this page, shows most of the ikat producing islands. Note the relative proximity of these islands to Timor, which has always had a measure of influence on the culture of the string of islands to the East, albeit a minor influence due to the lack of communication between the islands. Even these days, it can take anywhere from sixteen hours to several days at sea - in craft of doubtful seaworthiness - to reach them from Timor. The tragedy of missionary activityWhatever one may feel about the value of religion, few will not feel a sense of loss about the cultural destruction that missionary activity has brought about in the Moluccas (as it did on numerous other islands in the Indonesian archipelago, especially the ones that were small and remote, and therefore especially vulnerable - vide for instance Alor, Adonara and Lembata.) A crass illustration of this intentional destruction is given in Epithets and Epitomes, Management and Loss of Narrative Knowledge in South West Maluku, a study by Aone van Engelenhove on the role of artifacts as mnemonic devices supporting collective memory of traditional narrative:

Because the region remained undisturbed for a long time, its peoples failed to assess the new influences of Christianization and modernization in general. The Dutch [Protestant] missionaries perceived the statues and the rituals that went with them as exponents of the idolatry which they meant to eradicate. The islanders were encouraged to give up the statues, which were donated to missionaries and ministers, or simply destroyed. The last collective destruction took place in Tutukei (Leti) in the late sixties where all remaining statues were piled up in front of the Serwaru church and then burned. The know-how of their production was not transmitted to younger generations and consequently disappeared with the last practicing generation. The only medium to transmit knowledge on rou appears to be traditional textiles, which are still very much favoured in the region. Women, to whom weaving has traditionally assigned to, still learn how to make the motifs and dye them onto the cloth. The link, however, between the name of a rou and the 'narrative chunk' that goes with it has been lost. SW Malukans are very much aware, that they have lost a piece of knowledge that was stored in the artifacts they used to make and the stories they used to tell. Even so they acknowledge the power of names and songs. This awareness evoked an apotheosis of everything that can be regarded as a remnant from the past. This is especially salient on Kisar Island, the main center of textile production in the region, where the status of one's clan rather than the price one wants to pay determines what kind of cloth the client may expect. [..] The awareness of the importance of storytelling and the loss of narrative knowledge inevitably evoked a feeling of great frustration among the second and third generations. In their search for roots more and more SW Malukan migrants return to their islands of origin to find the knowledge that they have lost. [..] At the turn of the century it becomes more and more manifest, that SW Malukan culture will not survive in the next century." For assurance that indeed it will not, we can rely on further missionary activity. A web page on the site of the evangelist 'Joshua Project' with an interesting story about daily life on the island of Masela (off Babar) ends with the following call to prayer [condensed], a prime example of Christian arrogance and cultural superiority:

| ||||||||||||