Toraja textiles for use in funeral rites

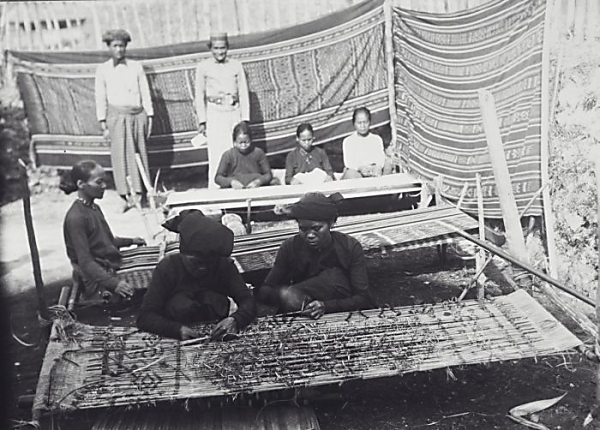

Torajan ikat weavers applying bindings to sets of warp threads. On Sulawesi, ikat textiles are mostly used as shrouds, and for display at ceremonies. Unlike anywhere else in the Indonesian archipelago, Torajan weavers, as seen here, often cooperate on a cloth. Photographer unknown, early 20th C., Tropenmuseum of the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT), Creative Commons Licence. The best known, and the most visually striking, Sulawesi ikat textiles are those made by the Toraja people, who occupy the mountainous central part of the island. Unfortunately we know little about them, as practically no one paid any attention to them before the onset of the 20th C., and there are few old examples extant. The most important weaving centres Ronkong and Kalumpang, lying in the most isolated highlands of northern Toraja were utterly devastated during the 'unrest' in the early 1950s, and most of their inhabitants driven into exile. As a result most of the region's material culture disappeared, though occasionally old cloths do show up in other parts of Sulawesi, sometimes with patterns that differ markedly from the Kalumpang/Ronkong vernacular, suggesting that in the past ikat weaving also took place in other parts of Torajaland. Unlike the rest of Sulawesi, Tanah Toraja, ('Torajaland') has not fully converted to Islam, but largely clung to its native animistic and megalithic religion, only partly succumbing to pressure to convert after 1909, when they began to be subjected to concerted efforts by Dutch protestant missionaries, and after the 1950s by Islam teachers. Still, even among the converted many traditional beliefs and customs have survived, including animal sacrifices and elaborate funeral rites that require the display and/or burial of traditional textiles. In earlier days large ikat cloths also played a role in the social sphere of the life of Tanah Toraja, serving for the payment of fines and as pledges of peace between feuding members of the upper castes. Bold patterns, contrasting coloursToraja ikat cloths are known for their bold geometric style of patterning which can evoke the work of American indians, and has helped create international demand for them. As the famous collectors, Holmgren and Spertus, write in Early Indonesian Textiles, "Toraja textile patterns are always exuberant, uncompromising, direct � never extraneously ornamental, and rarely figural." They used to be made from home-grown, hand spun cotton, involving natural dyes only, and the best modern ones still are. The Torajans use a fairly broad palette of colours, often in a contrasting arrangements. Black sets off the creamy white of undyed cotton, dark indigo is used next to baby blue, peach next to deep red. According to a regional source, to create a more vibrant red than provided by morinda, Toraja weavers sometimes add chilli powder to the dye mix, which may also contain dammar resin. Blue is achieved by mixing indigo, torae grass, and ink fruit. There is little evidence of patola influence, apart from the occasional use of tumpal borders. With few exceptions only indigo weft threads are used.Production versus creationIt may have been different in the 19th C. and before, but there is a long tradition here of weaving, not just for one's own community, but also for (barter) trade with other parts of Torajaland, so it was only natural for Torajan to start gearing themselves towards the tourist trade relatively early. They were already producing ikat, when women on most other islands were still creating. Emblematic for their attitude is, that two or three women may work on a cloth together - a world apart from the intensely personal, almost magical work done by most ikat weavers elsewhere in Nusantara.

Linking with an array of ancestorsLike many other Indonesians, converted or not, nearly all Torajans maintain the belief that after death they will be reunited with their ancestors, and their iconography speaks of this. One of the most common Toraja patterns is an array of interlocking hooks, called sekong. (See PC 064 and PC 065.) According to the dealer and Toraja expert, Thomas Murray, this motif represents the arms and legs of an ancestor extending from a diamond-like body. It symbolizes "how the newly deceased is linking in to an infinite array of interlacing ancestors." The sekong are often drawn with a white outline that is stippled in black or dark red.Some of the shrouds from Kalumpang are decorated with complex, dense patterns of elongated double arrows or rows of small diamonds in between rising lines. (See PC 066 and PC 067.) Characteristic of these cloths is their 'chaordic' nature: at first glance the pattern appears to be one ordered repetition, but at closer inspection the regularity proves to be subtly disturbed, creating a shifting, psychedelic imagery. The effect is as if the eye were making a vain attempt to bring order to the chaos of the universe, which gives imparts these cloths an extraordinary tension. Given the dominance of ancestor veneration in the Torajan belief system, it may be assumed that these patterns symbolize the intimate interwovenness of the living with the ancestors.  A wider shot of the same setting. Note the size of the cloth hung in the background. Photographer unknown, early 20th C., Tropenmuseum of the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT), Creative Commons Licence"

A wider shot of the same setting. Note the size of the cloth hung in the background. Photographer unknown, early 20th C., Tropenmuseum of the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT), Creative Commons Licence"

|