Batak ikat - the subtle art of people with a fierce historyAustere cloths with great levels of refinementIn Northern Sumatra, in the zone around Lake Toba, hemmed in between Aceh and Minangkabau, live the Batak people, six closely related tribes, the most well-known of which are the Toba Batak. All have developed an apparently deserved reputation for the practice of cannibalism - as distinct from headhunting, which used to be practiced in most parts of the Indonesian archipelago and informs much of the area's iconography. Marco Polo was the first traveller to remark on their dietary practices, which included consuming not just convicted criminals, enemies, and sundry undesirable elements, but also the elderly and infirm, with certain body parts (such as the soles of the feet) considered delicacies fit for a king, others mere food. Numerous reports from colonial times report the continued popularity of the practice, which was successfully repressed by the Dutch only in the early 20th C.Textiles play a very important social role in Batak communities as gifts at the various life cycle rituals. Strict rules determine the propriety or impropriety of certain types of textiles as gifts on specific occasions, considering the age and social status of the recipient. Most of the Batak tribes have been Christianized in the 19th C., beginning with those around lake Toba. A few of the southern tribes close to Minangkabau (that may resent being called Batak but have often been included under that nomer following the practice of the Dutch administration) are Muslim. In both Christian and Batak tribes adat elements continue to mark the belief systems and customs, and a substantial minority still adhere to the original agama si dekah.  Batak weaver in the village of Tapanuli. Photographer unknown, early 20th C. Tropenmuseum of the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT), Creative Commons Licence.

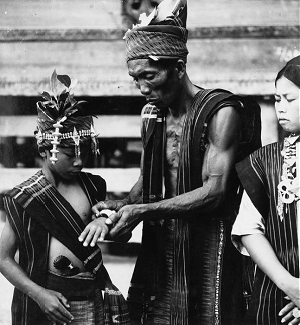

Batak weaver in the village of Tapanuli. Photographer unknown, early 20th C. Tropenmuseum of the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT), Creative Commons Licence.

Though their houses are often adorned with carvings of humans, animals and plants, the Batak never used representational elements in their textiles, limiting themselves to a range of basic geometric forms, most prominent among them a narrow arrowhead pattern.The Batak also limited their palette to indigo and morinda, both in various shades, but predominantly dark, with some accents in red. As a result, their textiles tend to have an austere appearance that most people find appealing only after some degree of familiarization. Minute distinctions spell great differences of meaningOnce one begins to develop a sensitivity to the subtlety of these cloths, the minute distinctions in motif and dye intensity and the extremely fine detailing, deep love for them may develop, as reflected in the market value of the better examples. As for those 'minute distinctions': though they may seem indeed minor to the western observer, to the Batak themselves they are highly charged

Two of the most sacred and prestige-laden of the Batak textiles are the ulos ragidup ('design of life') and the more rare ulos pinunsaan (see PC 047), both usually dark maroon with end patterns in supplementary weft. They play a central role in wedding ceremonies, being presented by a bride's father to the groom's mother to symbolize the bridegiver's superior status and, as Gittinger memorably describes it, his 'protective and fructifying' role. As is the case with some other Batak cloth, the ulos ragidup has distinct male and female endings, differentiated by the patterns in the supplemental weft. The spiritual power attributed to the ulos ragidup and some other Batak ikats is near boundless. A shaman may prescribe the weaving or wearing of one as a protection against physical danger, such as unexplained illness or pregnancy, or a protracted run of bad luck. In the past ulos ragidup even had oracular use: seers would read the future in their patterns. Fading traditionsThough the ritual role of ikat is still kept alive in the Batak lands, especially in the mountainous interior, as elsewhere in Indonesia the art is in decline. One of the symptoms is that tying, dyeing and weaving are now often executed by different women, as few still master the whole range of required traditional skills. We also see a regional shift, or rather a concentration of the weaving in one area: since the mid 1900's most of the weaving is done by the Toba Batak, who will produce cloth in Karo, Simalungun or Angkola style upon demand, mostly on mechanical looms in small factories, using chemical dyes - the same pattern of degenerative development that we see in most parts of the archipelago where ikat still has a role in ritual or social life. | ||||||