The middle of nowhere - and its awe inspiring art

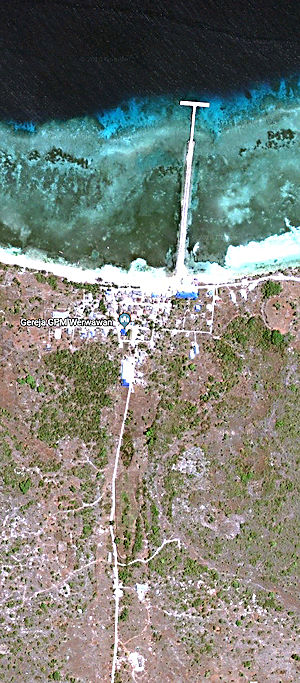

What fascinates us about tiny specks in the ocean such as this, is how people manage to survive there, and manage to develop artisanal skills. One can only be deeply in awe of such people, who no doubt lead a hardscrabble existence in a zone with a dry season that lasts for months, so that both agriculture and raising livestock are difficult; where fishing - in a sea that is notoriously treacherous - is almost certainly the main source of protein; and where there are practically no opportunities for trade. Given these facts of life one would expect any textiles produced on the island to be extremely basic. Yet as our specimen shows, both the design and the weaving are on a par with larger and much less remote islands such as Adonara and Alor. Remarkably, even here in this remote outpost at the very extremity of the Indonesian archipelago, we see the influence of Indian patola trade cloths in the design: the main ikated bands of this one cloth end in There is a set of pictures on Panoramio which give some idea of what the island looks like, and how it would be to live there. If you have any more information on the island and or its textiles, please share your expertise. LiteratureProbably the best source of information on the archipelago of which Lakor forms a part is Forgotten Islands by De Jonge and Van Dijk. We have yet to find literature specifically about Lakor and its textiles, but we did find an interesting paragraph on the internet regarding the island: "The mediate expulsion of evils by means of a scapegoat or other material vehicle, like the immediate expulsion of them in invisible form, tends to become periodic, and for a like reason. Thus every year, generally in March, the people of Leti, Moa, and Lakor, islands of the Indian Archipelago, send away all their diseases to sea. They make a proa about six feet long, rig it with sails, oars, rudder, and other gear, and every family deposits in its some rice, fruit, a fowl, two eggs, insects that ravage the fields, and so on. Then they let it drift away to sea, saying, "Take away from here all kinds of sickness, take them to other islands, to other lands, distribute them in places that lie eastward, where the sun rises." From the famous work The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion, by Sir J. G. Frazer, first published in 1890. The book is available online at Bartleby's: URL Another indirect source is Epithets and Epitomes, Management and Loss of Narrative Knowledge in South West Maluku, a fascinating article on oral traditions in the region by Aone van Engelenhove: URLVan Engelenhove explains that artifacts, such as the ikat textiles, in these parts served to support memorisation of traditional narratives: "The worldwide admired handicraft of the islanders, the statues, the textiles and the goldsmithry primarily functioned as a means to fixate the motifs and ornaments with which the narratives were memorized. In this perception it is understandable that these artifacts whose importance was well acknowledged by the islanders, were easily sold or bartered (Jacobsen 1896). The artifacts themselves could be easily replaced by new made ones. The rou [traditional motif], however, being the counterparts of names on artifacts, were not for sale." Elsewhere he writes: "The only medium to transmit knowledge on rou appears to be traditional textiles, which are still very much favoured in the region. Women, to whom weaving has traditionally assigned to, still learn how to make the motifs and dye them onto the cloth. The link, however, between the name of a rou and the 'narrative chunk' that goes with it has been lost." This means that in terms of cultural development Lakor is a 'normal' island in the Indonesian archipelago, as the same is happening almost everywhere else: the patterns remain, but what they stand for disappears from the collective memory - a process that constitutes an irretrievable loss not just for the islanders, but for mankind. We still look at these pieces, but as time goes by we will less and less about what they mean. Being conscious of this development should spur us on to document what we can and preserve not just the material objects, but also whatever knowledge we may possess about their meaning - and in some cases, feed them back to the source. | ||||||||