What is ikat?

Textiles that reflect the organisation of the cosmos

Ikat (pronounced ee-kat), a Malay-Indonesian word meaning 'to bind', 'to tie', in textiles denotes a cloth-making process in which threads are resist-dyed before weaving. In English, the term can refer both to the technique and the product. Grouped in tiny bundles, threads in areas mapped during the design process are wrapped in watertight strips of material to prevent colour penetration. After dyeing, the wrapping, or 'resist', is removed, and the procedure is repeated for a second colour, then for a third, and so on. Finally, the colourful, patterned threads are woven together with others, usually unpatterned, on a loom - in most cases a simple backstrap loom. |

|

| 6th C. bronze found on Flores showing a woman nursing while working at an archaic foot-braced body-tension backstrap loom. National Gallery of Australia. | |

While practiced in many parts of the world, ikat found its widest dissemination and greatest diversity in the Indonesian isles. Here also it appears to be most intensely imbued with meaning. "For Indonesians," as Mary Hunt Kahlenberg writes in her introduction to the classic Textile Traditions of Indonesia, "the art of weaving - the intercrossing of the warp and the weft - symbolizes the structure of the cosmos: the warp threads fastened between the ends of the loom represent the predestined elements of life; the weft passing in and out and back and forth denotes life's variables." This statement typifies Indonesian ikat textiles: they are never just attire, never just material. There is always a spiritual level and in many Indonesian island societies, the spiritual, magical, level is the dominant factor.

Indonesia is a predominantly Muslim country, but ikat cloths overwhelmingly originate from regions where Islam has not penetrated to any extent. (Notable exceptions being Southern Sumatra and to a lesser extent Lombok.) On Bali and in a small part of Lombok most people are Hindu. Most of the people in the Lesser Sunda Islands, a chief ikat producing region, and the Moluccas, are Christian. A dwindling number there, on Borneo and on Sulawesi are what used to be called pagan: animists, believers in spirits, ancestors, forces of nature. This decrease was everything but spontaneous. At Indonesia�s independence, five religions were officially recognized: Islam, Protestantism, Catholicism, Hinduism and Buddhism. During the wave of anti-communist pogroms in 1965, not adhering to one of those would lead to accusations of being atheist, which was equated with being communist, and exposed one to 'capital punishment, or rather murder by mobs. As a result nearly all Indonesians identify themselves as belonging to one of the approved five faiths. But underneath the monotheistic faiths traditional belief systems are very much alive. Ancestors are venerated nearly everywhere, spirits feared and placated, forces of nature respected with religious fervour. Thus it is not at all strange to find that Indonesians of all religions consider certain types of textiles sacred - ikat textiles especially - hold them in deep veneration, and even ascribe them curative and other supernatural powers.

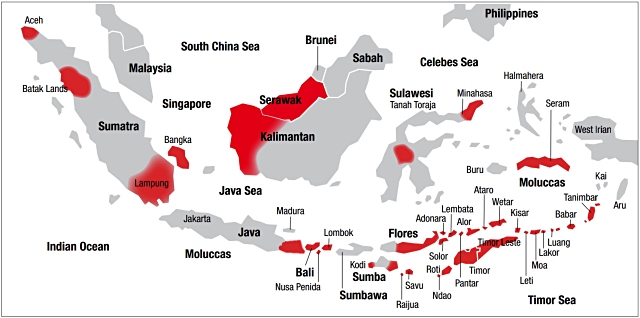

Chief areas of ikat production in the Indonesian archipelago. Map courtesy Carpet Collector, which produced it to accompany one of Peter ten Hoopen's articles for the magazine - a modified version of map graciously provided by Chris Buckley. All borders are approximate, no political implications intended.

Chief areas of ikat production in the Indonesian archipelago. Map courtesy Carpet Collector, which produced it to accompany one of Peter ten Hoopen's articles for the magazine - a modified version of map graciously provided by Chris Buckley. All borders are approximate, no political implications intended.

Astonishing variety

The variety in styles we find in Indonesia is truly astonishing. The cloths of two neighbouring islands can be so far apart that no one except an expert versed in the vernacular of traditional motifs and their building blocks would think of placing them in each other's vicinity, and even on the same island there can be a stunning diversity. This must originally have been caused by lack of communication: as a result of the often mountainous and jungle-clad terrain, travel on the islands used to be extremely difficult, and on many still is a challenge today. In the period of colonial domination cultural distinctions became more marked as the Dutch overlords manipulated local rulers by means of shifting alliances. This strengthened the need for clearly expressed identity.As a result of this set of natural and human causes, the island of Flores, 350 km long, has seven major centres of ikat production with markedly different styles. The indigo cloths from the Bajawa region in Western Flores, with their stick figures remiscent of drawings made by cave dwellers, bear no resemblance to the refined geometry of the cloths from the Lio people in South-Eastern Flores, which again are very different from cloths produced in the Sikka and Ili Mandiri regions.

Unifying elements

On the other hand, there are elements of design that seem to pass through the cultural barriers, connecting the entire Indonesian archipelago. And curiously, the most striking of those shared elements are not indigenous, but derived from a type of technically advanced double-ikat cloth called patola (sing. patolu) that was imported from the Indian state of Gujarat, probably starting as early as the 17th century.These striking cloths, often four meters long, were acquired for ceremonial use at the courts of rajahs, radens and lesser rulers throughout the islands - a use that is still continuing. Various design elements derived from these patola are found from Sumatra in the West to Tanimbar in the far East of the Indonesian archipelago, serving to connect what would otherwise have been a disparate collection of idiosyncratic art forms.

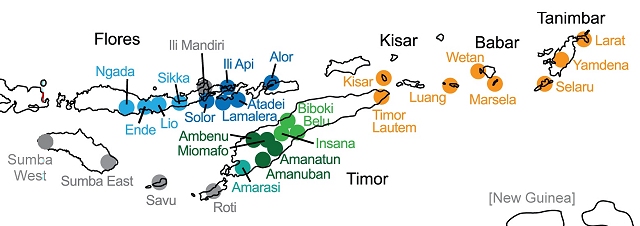

The ikat regions of southeastern Indonesia grouped by similarity on the basis of shared visual 'vocabulary'. From Christopher D. Buckley's phylogenetic study of the dissemination of ikat through Southeast Asia: URL. Slightly modified by gracious permission of the author.

The ikat regions of southeastern Indonesia grouped by similarity on the basis of shared visual 'vocabulary'. From Christopher D. Buckley's phylogenetic study of the dissemination of ikat through Southeast Asia: URL. Slightly modified by gracious permission of the author.