Iban pua - the pinnacle of ikat weaving in Indonesian archipelagoThe Iban pua kumbu (blankets) from Borneo represent the pinnacle of ikat weaving in the Indonesian archipelago. While there are other areas where the technical finesse may approach or even equal that of the Iban - the cloths from the Lio region in Flores and the Balinese geringsing from Tenganan come to mind - the complexity of the Iban patterning has no equal anywhere in the region, or indeed the world. The meandering, intertwining patterns, which to the Western, untrained and uninitiated eye are hard to analyze, leave alone to memorize, surpass even Persian carpets in the level of their intricacy. Also striking, from an art-historical point of view, is the level of stylization. Most primitive art starts representational, and it is only in later stages of development that the artists dare to depart from that which is easily recognized: gradually reducing, accenting, reinventing familiar shapes. This aspect of Iban textile manufacture suggests that it is a very old art form, that has been central to the community for many centuries.

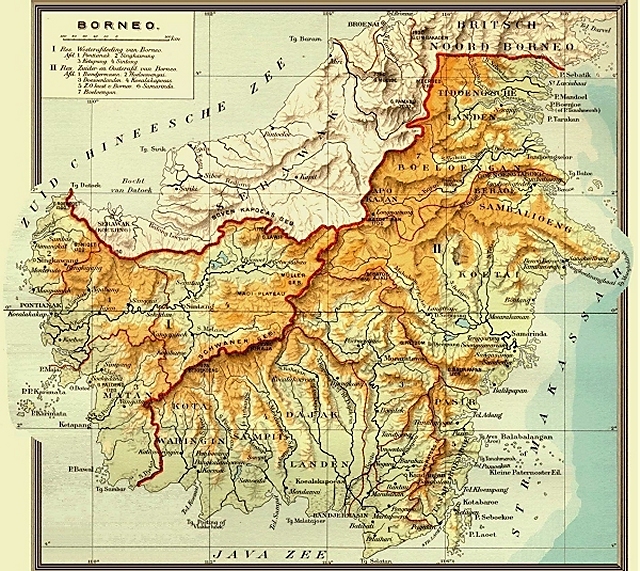

Many of the best pieces, and the majority of those in our collection, come from Sarawak, the North-Western part of Borneo that is now a Malaysian state, mostly from an area called Second Division, comprising the Batang Lupar and Saribas River systems. All of the Iban textiles in the Pusaka Collection are pre-war, most dating from the earliest decades of the twentieth century. Part of the fascination of collectors with Iban pua certainly is triggered by tales about their association with headhunting. As there are widely diverging views on the veracity of such tales, it seems best to let this issue by dealt with by a local expert. The Iban politician and expert on weaving culture, Vernon Kedit, whose lineage includes generations of master weavers, graciously allowed inclusion of the below exposé, earlier posted on tribaltextiles.info. Debunking a mythBy Vernon KeditThere have been a lot of stories about pua being used to receive the fruit of headhunting expeditions. But the idea of a bloody head dripping with blood and then wrapped up unceremoniously in a pua kumbu is really a myth. A very gory myth that works well with the romanticism of the era. In actual fact, when warriors return with trophy heads from a raid or battle, they do not bring their trophy heads directly into the longhouse. They would clear an area within earshot of their longhouse, and make camp there for seven nights. The trophy heads would be cleaned and then smoked over a gentle fire to dry them out. At the same time, the women back at the longhouse would start preparing the feast and most importantly, repairing or re-starching their prized pua kumbu for the enchaboh arong ceremony (the ritual of receiving a trophy head). Everybody would know that the warriors returned safely but everybody would keep up the pretense that they are still away on the raid. On the eighth morning, the warriors would dress up in their finery (presumably smuggled out of the longhouse to them by a precocious younger brother or cousin) and begin their procession from the clearing to the main stairs of the longhouse. Music would be played on gongs (also presumably smuggled in the dead of night the night before from the longhouse) as the men make their victorious approach, not unlike jubilant Caesar entering Rome to much fanfare. The women would also have woken up early and prepared themselves and all the ritual objects for the ceremony. Food and wine would be waiting in the longhouse communal gallery. Maidens would dress up and wait to be courted by the brave warriors. Upon reaching the stairs, the lead warrior would present his trophy head (or heads) to either his wife (if he is married) or his mother (if he is unmarried) with much shouting and yelling of war cries. The woman receiving the head would be waiting with a large plate in her arms over which a pua kumbu would be meticulously draped. The angle and the manner is very important as the most potent motif on the pattern must touch the base of the trophy head when it is placed on the pua. The trophy head, by now fully dried out and hair perfectly combed, would be placed carefully on the pua kumbu in the plate. The man would hold the head above the cloth while the woman would adjust the angles of her arms to find the best 'repository' position for the head. The pua kumbu is not wrapped around the head. It merely serves as a base cloth for the head. The woman would then welcome the head as she would welcome a new born babe, singing a lullaby to the trophy head as she gently cradles and rocks it (known as the naku pala). It is at this point that the powerful spirit of the pua is then believed to envelope and negate/neutralise all negative forces of the enemy's head. Then the next warrior in rank would do the same, until all the warriors have presented their heads. No wild dramatics. All very civilised. Then the heads are taken out to the tanju (open air verandah) where the enchaboh arong ceremony proper begins. After chants and prayers and blessings culminating in the climactic ritual bite (the women bite the heads as a sign of victory over the enemy - this bit, I agree, is somewhat gruesome and horrific), the heads would then be placed in rattan baskets and then hung in the longhouse over the entrance of their respective owners' bilik. That is why you will never have blood stains on any pua kumbu for the simple reason that all trophy heads are smoked and dried for seven days and nights before they are ceremonially presented to the longhouse. Any stain a dealer tells you is a blood stain is an outright lie to inflate his profits. Or if there really is a stain, it would most probably have come from food or drink spilt on the pua during festivities. The only time I have seen real blood stains on a pua was when a slaughtered sacrificial cockerel in its death throes flicked a few droplets of its blood onto the nearby displayed blanket during a miring (blessing ceremony), which annoyed its owner immensely. Nasty business as animal blood has a horrid stench. We like our cloths clean and unblemished, more so if they are masterpieces of high status. So if you hear fanciful stories of human blood stains on a pua kumbu, just smile and enjoy the tale. This exposé was first published on www.tribaltextiles.info, and republished here with the author's gracious permission. In another post Kedit wrote [first line edited to fit]: "Weaving in the Saribas continued right into the middle of the 20th century where it saw its zenith, as demonstrated by the textiles woven by my fore-mothers whom used very fine bought threads to further refine and develop various weaving techniques. Weaving only declined after the end of the 2nd World War with the advent of 'modernisation'. The Japanese Occupation which stalled trade during the war also contributed to the slowing down of weaving as bought threads became scarce. Women focussed on surviving the war and taking care of their families rather than weave for leisure and status. The British colonisation that followed placed an emphasis on education and many young Iban girls flocked to schools instead of staying in the attic to weave. By the 60s, one would have been hard pressed to find any woman weaving in the Saribas, although weavers still lived but had little inspiration or need to take up the loom. A 'new dawn' had come with Independence in 1963 and things of the past were put aside. The flourishing of Christianity in the Saribas also replaced Iban rituals and the attending need for ritual accoutrements, especially textiles. All is not lost, though. There is now a 'revival', which began sluggishly in the 90s but is now gaining momentum as retired professional women from the Saribas take up the loom to continue the tradition of their fore-mothers, and weave for leisure and status" |