The geringsing double ikat of Tenganan

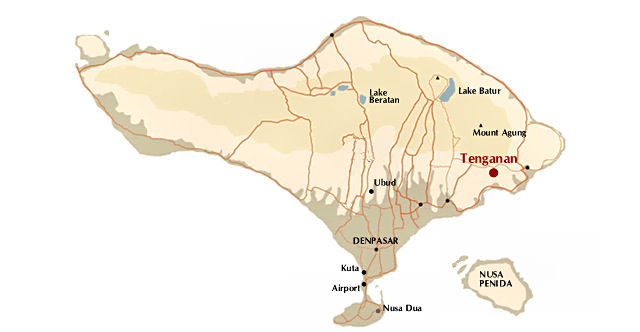

Tenganan, located southwest of Amlapura, near Bali's South-Eastern shore of the island, is populated by Bali Aga who are believed to have originated from the pre-Majapahit Bali kingdom of Pejeng, settling in Tenganan before the occupation of Bali by the Hindu Javanese who arrived in the 15th as the Majapahit empire collapsed under Muslim pressure. They maintain an archaic, highly ritualized form of Hinduism, and feel that they are superior beings, selected by the god Indra to lead an ideal, exemplary, essentially holy life. The way the Bali Aga of Tenganan implement Indra's divine plan for his chosen people makes it easy to see how they could maintain their belief and sense of superiority over the centuries. They see it as their primary duty to play an active role in rituals honouring their gods and ancestors, and assuaging their demons, and in order to maintain the required purity largely shut themselves off from the outside world with all its corrupting influences. Though some aspects of their society may be criticised (for instance their reduction of the infirm to pariah status), there is much to admire. Indra's plan was to make this village serve as a microcosm of the world. As Urs Ramseyer writes in his contribution to Textiles in Bali, the people of Tenganan "were instructed to use every available means to keep it pure and clean, and the concept of territorial, bodily and spiritual purity and integrity is of paramount importance to the culture of this village - reflected not only in a ritual intercourse with the surrounding territories (purifications, exorcisms), but also in the notion [found equally in Indian yoga philosophy, tH] that only if a person is healthy in body and spirit may he or she participate in rituals. [..] Ritual apparel attests to the wearer's divine entitlement to memberships in the Tenganan community, and evinces one's purity and eligibility to take part in communal rituals. Such purity is in turn effectively shielded from harmful or impure influences from outside by the magical, protective power of the cloths." This protection is sought especially during rites of passage, as the people of Tenganan transition from one life phase to the next. The word geringsing itself eloquently enunciates the textiles' attributed powers of protection: gering means 'decease', and sing means 'no'. This belief in geringsing's protective qualities is shared by all Balinese and the inhabitants of many other islands, who cling even to tiny fragments of geringsing, sometimes smaller than a postage stamp, believing that they offer protection from illness, black magic, and other evils. Part of this admiration, or even worship, no doubt stems from the extreme difficulty of the double ikat process, which is immediately recognized by other peoples with an ikat weaving tradition. But another part probably derives from tales, turned legendary in the retelling, about the Tengananese way of life, which can seem like a never ending cycle of ceremonies, all requiring elaborate dressing up, with double ikat wraps and sashes, and is inherently sacred. Geringsing accompany the Tengananese from the cradle to the grave. They receive their first cloth at the ritual first hair cutting, and the next during the rite of passage in which they are admitted to the village's youth association, when they are carried on their father's shoulder wrapped in a geringsing. In all subsequent ceremonies, such as the initiation rite, teruna nyoma, the teeth filing preceding marriage, and the wedding itself, the use of geringsing cloths, ideally undamaged, is essential. At death, the deceased's genitals are covered with a geringsing sash, defiling the cloth, which is then usually sold off. After death a purification ceremony, muhun, is held for the soul, symbolized by a palm leaf with sacred inscriptions, which is folded in a geringsing.  Early 20th C kamben geringsing with motif pat likur isi. Pusaka Collection, No. 059. Geringsing is very old. It is mentioned in poems from the 14th C., and then already attributed protective powers. According to one text the first Majapahit king, Raden Wijaya, gave his warriors geringsing sashes to protect them in battle, and another describes a king riding in a carriage made of such magical cloth. Poetic licence.... According to Georges Breguet, one of the world's most passionate and knowledgeable collectors of geringsing, there are about thirty different patterns, most of them consisting of repeating small motifs like lozenges, stars, crosses, and stylized flowers, such as the holy frangipani, cempaka. The more striking kinds, usually called the wayang type, show large radiating mandalas that look like ancient Hindu temples seen from above, and human figures based on the Balinese shadow play, wayang kulit. The colours are muted, usually limited to brick red (morinda), dark purple bordering on black which is obtained by overdyeing of morinda with indigo, and the natural écru of the cotton. In the wayang type only the latter two are used. All are made with a loose tabby weave, which makes them both fragile, and semi-transparent. Geringsing are sometimes beautified with non-traditional end sections in silk embroidery, but this is done only outside Tenganan as it makes the textiles unsuitable for ceremonial use in the village. Curiously, the stunning Tenganan textiles were discovered by westerners only several centuries after they arrived in the Indonesian isles. There is no earlier record than that by the Dutch artist Wijnand Nieuwenkamp who was so stunned by two geringsing cloths that he found in a box of textiles that he bought in Tabanan for the Ethnographic Museum in Leiden, that he decided to go to the source, and in 1906 made a journey (one is tempted to write 'pilgrimage') to Tenganan. These days uncounted thousands make the same journey, crowding the narrow streets of the village to gawk at the weavers producing simple non-sacred cloths for the tourist market, and at the few collectable pieces that occasionally come on offer - at prices that reflect an acute awareness of global market values. |