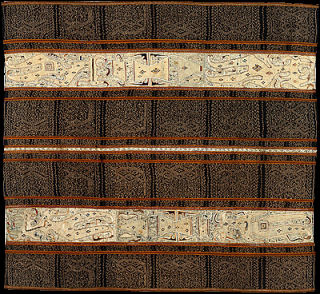

Lampung, home of precious tapisLampung province lies on the southern tip of the island of Sumatra. The region earned an early renown for its rich weaving tradition, and its cloths are eagerly sought by collectors, but ikat is used in only a few of its various types of textiles � notably the ceremonial tubeskirt called tapis, where it is nearly always combined with silk embroidery. Weaving in the region may date back to the first millennium AD when the Buddhist Srivijaya empire, with its capital at Palembang in south Sumatra, was the undisputed hegemon in southeast Asia. Srivijaya attracted monks, ambassadors and traders from as far away as China, Cambodia, and India, and from the 8th till the 12th century served as the region's chief hub of cultural interchange. As a result, as Thomas Murray phrases it, "in the textile art of the area we witness cultural and aesthetic hybridisation at its most fertile, both esoteric and compellingly beautiful." Heirlooms with supernatural powers

What their motifs stand for is likewise shrouded in mystery. As the legendary collectors Holmgren and Spertus write in Early Indonesian textiles, "their complex iconographic content remains almost entirely conjectural". They do speculate that the embroidered amoebe-like shapes, which with some imagination might be seen as anthropomorphs, may represent spirits. Many of the best cloths were made by the Paminggir, Abung, Krui, and Pesisir people. Production was particularly prolific in the southern Lampung Kalianda Bay area and in northern Lampung among the Krui aristocracy. But the exact provenance of most tapis may forever remain shrouded in mystery because their use in bridal exchanges assured that over time many of them ended up far away from their place of manufacture. The mystery has almost certainly deepened as a result of Sumatran antique dealers' interest in spreading disinformation about the source of these precious, sought after cloths. Possibly older than originally thoughtIt now appears that the best pieces were made in very remote mountain villages - and that they are older than originally thought. Whereas fifty years ago most were routinely identified as 19th C., some, based on carbon dating are now taken to date from the 18th or 17th C, and a few even earlier.As the reliability of carbon dating is contested, such early dating cannot be accepted without taking other factors into account, particularly when it impacts either curatorial prestige or commercial value. Uncontested is, that these fine textiles were produced in a very remote, mountainous area, where general living conditions must have been, if not poor, then at least very challenging. Because they have been considered precious pusaka since time immemorial and treated with reverence, the Lampung tapis were always very well cared for, rarely even displayed, and as a result often look fresher than most textiles in the tropics that are only a fraction of their age. Nature, economy and religion conspired to cause tapis's demiseThe production of fine textiles increased in the late nineteenth century as Lampung became prosperous due to its pepper cultivation and related industry and trade, but the devastating eruption of the Krakatau volcano in 1883 destroyed many weaving villages, especially in the Kalianda area. In the early 1900�s continued conversion to Islam decreased the importance of the region�s traditions, including those requiring special textiles, while the collapse of the pepper trade ruined the buying power of the ruling classes. As a result, by the 1920�s, the production of high quality Lampung textiles had ground to a halt. As a result, antiques are de facto the only Lampung cloths available - sporadically. |