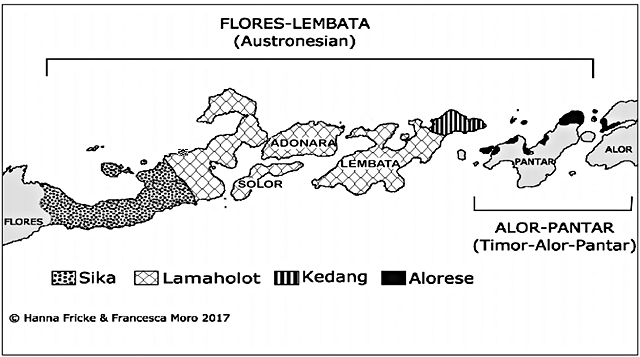

Lamaholot people, dispersed over several islands

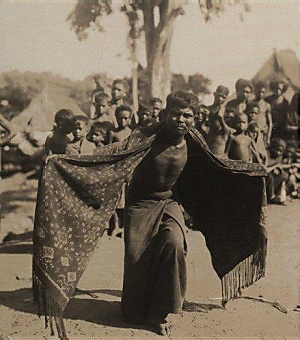

Although the speakers of Lamaholot usually think of it as a single language, it is better understood as a dialect chain with substantial differences between some of the 30 odd dialects - so substantial in many cases as to make them mutually incomprehensible. Some experts in fact speak of 18 different languages plus a few dialects. On the small island of Adonara, as Ernst Vatter reported in the early 20th C., people from some neighbouring villages do not understand each other, and at markets need interpreters from a third village to help them communicate. These days almost all Lamaholot speakers are bilingual or multilingual: they learn Indonesian as the official language of the Republic of Indonesia at school, and some of them also speak local languages such as Sikka and Larantuka Malay. Culturally the Lamaholot have much in common, for instance in their traditions concerning weddings, but this commonality is not immediately apparent. If fact we are immediately struck by their diversity, especially as manifested in their textiles. The ikats from Solor, Lembata and those from Ili Mandiri in eastern Flores for instance are so different from one another that they might have been made on another continent. Lamaholot religious beliefsThe Lamaholot are also known as Ata Kiwan (a term serving as the title for an eponymous study by Ernst Vatter), Holo, Solor, Solot and Solorese. The great majority are Christian (80% Roman Catholic), although many, especially in some coastal communities, are Muslim. Quite a number are true to their traditional faiths, including ancestor cults and a monotheistic faith around a deity who represents the celestial bodies and the earth. The Lamaholot name for God is Lera Wulan, meaning Sun Moon. His female complement is Tana Ekan, Earth. In a typical process of co-optation of preexisting deities, Lere Wulan is now associated with the God of Christianity and with Allah of Islam. Lesser spirits, nitu, inhabit tree tops, large stones, springs, holes in the ground and other remarkable natural features. Other deities of importance for the Lamaholot are Ili Woka, the God of the Mountains, and Hari Botan, the God of the Sea.Traditional priests and healers called molang play roles of importance in the communities, as do male and female witches, called suangi and menaka. People have two souls, tuber and manger. Upon death the tuber joins Lera Wulan, or is eaten by a nitu or menakaa. The manger goes to the land of the dead, to be reborn on the next level below. After several cycles of life and death, the person completes the cycle of births and rebirths, and begins again.  Lamaholot people in the whaling village of Lamakera on Solor with a captured whale. Photographer unknown, early 20th C. Tropenmuseum of the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT), Creative Commons Licence.

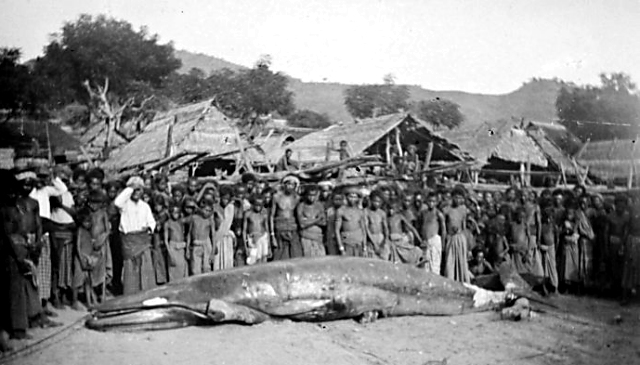

Lamaholot people in the whaling village of Lamakera on Solor with a captured whale. Photographer unknown, early 20th C. Tropenmuseum of the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT), Creative Commons Licence.

Economy and social systemMost people in the interior depend on swidden agriculture for subsistence, those on the coast mostly on fishing. The villager of Lamakera on Solor and those of Lamelerap on Lembata are big game fishermen, going for whale, manta ray, shark and dugong. The staple foods are maize, rices, tubers and vegetables. Cotton, indigo (for blue dye) and morinda (for red dye) are produced locally, as are rare plants from which yellow and green dyes are extracted in small quantities. Coconut palms are cultivated for copra and coconut oil, and to provide building materials. Coastal communities traded fish for agricultural products and livestock such as goats with communities from the interior.The Lamaholot, like most Indonesians, live in extended families, often including grandparents, younger brothers, cousins and other dependents. Inheritance is usually patrilineal, but the close relatives of the mother, especially her parents, control the well-being of her children and enjoy an esteem by them bordering on the esteem given to divinity. Weddings traditionally required substantial alliance gifts, notably including elephant tusks for wife givers and high quality ikat textiles for wife takers. In these days, motor cycles, building materials, appliances, and cash have replaced tusks, which now are very rare - most of them having been sold off to dealers scouring the islands for valuables at bargain prices. Divorce is easily arranged, except for Catholics, the dominant religious grouping. The Lamaholot used to have a distinct system of ritual leadership, where four ritual leaders shared the power to rule over the people: the kepala koten (kepala meaning 'head') was in charge of internal village affairs, the kepala kelen took of the external affairs. The other two positions, hurit and marang, had advisory functions. Other influential village elders ensured that none of these leaders got too powerful. Social distinctions based on wealth existed, and exist, but today are not easily perceivable. Slavery was once prevalent, as it was on Sumba and other islands in Nusa Tenggara Timur, but has been abolished. There is no longer a nobility as such any more either, but there are some clans built around former ruling lineages that are regarded as more powerful than others, and have more wealth, particularly land, and often maintain the title of rajah. Some of these rajahs can be quite poor by western standards and for an outsider are hard to distinguish within the local population. In our dealings with them they appeared quite keen to sell their heirlooms, specifically patola, to improve their material wellbeing, e.g. to build an extension to their house or buy a second hand motorbike. Because of all the old tales of fabulous wealth at oriental courts, is sometimes hard for westerners to grasp that, also in colonial times, many of the local rulers, especially on dry, infertile islands, actually lived on the edge of destitution. Little has changed since those days, except that they have now also forfeited most of their status. Since independence, petty nobility nearly everywhere have lost office, power, and influence. The old symbols of power and prestige, such as patola cloth, also no longer carry the weight they once had. In a remote village where electricity is a remote dream, a small generator provides more status than an old textile, whatever its traditional associations. Lamaholot ikat textiles

According to Ruth Barnes (see below), who spent considerable time in the area, the rata stands for the threads of kinship and descent and must not be cut for it to retain its validity as bridewealth. Other sources have interpreted the unwoven gap, left uncut, to stand for the virginity of the bride, but as virginity is not as closely guarded as it is in some other (mainly Muslim) parts of the Indonesian archipelago, this may not have basis in fact. Such a cloth with a continuous warp left uncut obviously is not suitable to be turned into a sarong and is never used for attire. The colour is prescribed: it must be predominantly red, méan. The word stands not just for the colour red produced from the roots of Morinda citrifolia, but also for beautiful, strong, healthy - a set of connotations similar to the Russian krassivo. It is also associated with blood and warfare. For this reason, preparation of the dye must be left to experienced women who know how to handle powerful material, as those who cannot handle to force may lose their sanity. Given this context it obvious that any cloth that may be referred to as méan is regarded as imbued with spiritual power. Unfortunately, few if any of such cloths remain in local hands. In 1982 Ruth Barnes found that on Western Solor, once home to some of the best ikat in the Lamaholot region, kewatek méan could hardly be found anywhere. In the area around Ritaebang there were only two in existence. As a result of a few decades more of eager sourcing by dealers combined with dire economic circumstances on the island we can safely assume that by now there is not a single one left. On other Lamaholot islands the situation is very similar, with Lembata perhaps offering the most hope for survival of at least some part of its tradition. Literature on Lamaholot ikatThe most important source of information on the culture of the Lamaholot people remains the venerable Ruth Barnes. Her Without Cloth We Cannot Marry is a core document for the understanding of Lamaholot culture, particularly with regard to the textiles. There is scant other information on the Lamaholot people and their ikat textiles, scattered over a few books and a small number of scientific publications not easily accessible for the general public.Map of Lamaholot area

©Peter ten Hoopen, 2025. The contents of this website are provided for personal, educational, non-commercial use only. No part of this website may be reproduced in any form without explicit permission of the copyright holder. |