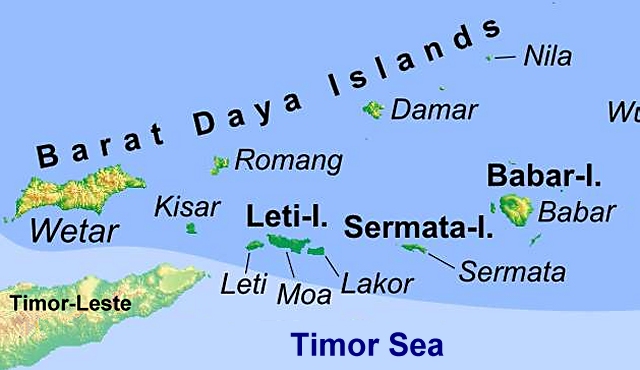

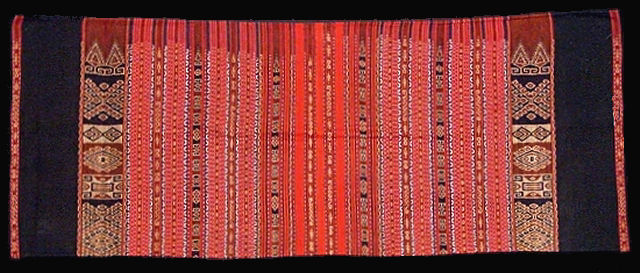

Tiny Kisar, home of excellent ikat textilesKisar, is one of those amazing Indonesian places that are tiny and remote, mere flecks in the ocean - and home to a great artistic tradition. Locally known as Yotowawa, Kisar is a small (81 km2) island in the Southwestern Moluccas or Barat Daya Islands, lying just 25 km north of Timor. The landscape is dominated by lontar palm (Borassus flabellifer) savannah. The island derives its name from the Kisar word for white sand, which the Dutch, who first colonized the island, decided to adopt. Kisar is closer to Timor than to the rest of the Moluccas, not just geographically but also culturally. There are two distinct languages spoken on the island: Kisar, also called Yotowawa or Meher, and Oirata, which is closely related to the Fataluku spoken in the Lautem district of East-Timor. As might be expected from two regions where similar languages are spoken, comparison of Kisar textiles with those from Los Palos in Gauteng, as we shall demonstrate below, shows up clear resemblances. Kisar has a Timorese feel, with villages scattered in the dry, scrubby interior, rather than along the coast, as is common in most parts of the eastern Indonesian archipelago. The Dutch East Indies Company (VOC) established a fortified base here in 1665 to support their activities in the South Moluccas, and appointed the first of a dynasty of mixed blood local rajahs through whom they would rule - to the chagrin of local chiefs who had never known anyone to lord it over them.  Early 20th C. ikat sarong from Kisar. As this cloth was almost certainly made with natural dyes, the colours in reality are probably more muted, similar to those on Pusaka cloth No. 138. Collection Tropenmuseum of the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT), Creative Commons Licence.

Early 20th C. ikat sarong from Kisar. As this cloth was almost certainly made with natural dyes, the colours in reality are probably more muted, similar to those on Pusaka cloth No. 138. Collection Tropenmuseum of the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT), Creative Commons Licence.

Dutch stronghold serving the spice tradeThe Dutch remained on the island for some 130 years, using the island as a regional stronghold to protect their spice trade, and seeded themselves actively, creating a sizeable Eurasian community, commonly referred to as the 'Kisar mestizo'. Their descendants, usually well educated, have ruled the island every since, either as rajahs or lesser chiefs. Many Dutch family names survive, including Joostenz, Wouthuysen, Caffin, Lerrick, Peelman, Lander, Ruff, Coenradi, van Delsen, Schilling and Bakker - a name that may have humble origins (Bakker stands for 'baker'), but here is strongly associated with royalty. The first raja of Kisar was Cornelis Bakker (who also ruled Wetar, Roma and Leti island through his brothers) and there were Bakkers on the throne up to and including the current, twelfth Raja of Kisar, Johannes, whose role, under the Indonesian republican constitution, is merely that of a ceremonial dignitary consulted on matters of tradition.In 1795 the Dutch were driven out by the British, in 1803 the island came under a joint Dutch/French rule, and in 1810 fell back into British rule. In 1817 Kisar was returned to the Dutch, who abandoned the island in 1819. Since that time the Kisarese, essentially independent, upheld close ties with their Portuguese, Topasses (mestizo) and Timorese neighbours on Timor.

Inhabitants of Kisar, early 20th C. The men appear to be of high rank. The man second from right wears what may well be a patolu. Collection Tropenmuseum of the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT), Creative Commons Licence.

Failed struggle for independence, integration into IndonesiaAfter World War II, which gave rise to Indonesia's independence in 1946, Kisar formed an active part of the group of South Moluccan islands which declared themselves independent, under the name Republik Maluku Selatan, but this republic failed to generate international support, even from the Netherlands, with which it wished to establish close cooperation, and Indonesia simply integrated the islands. The idea of the RMS may have died in practice, it remains alive in the islands' community, albeit mostly among the elderly - and survives in the fake postage stamps 'issued' in the years of notional independence by an German/American stamp dealer Henry Stolow.One of the reasons for the South Moluccans' desire for independence was that they had for centuries loyally served the Dutch colonial rulers. Christianized from the early 17th century on, and often well educated, the traditionally warriorlike South Moluccans served the Dutch administration in many crucial functions, not least in the military. As a result they deeply distrusted the Muslim Javanese who dominated the government of the Indonesian republic and in turn were despised by many other Indonesians as collaborators and usurpers. It appears that these days the Indonesian facility to forget the unpleasant has smoothed out most of the wrinkles, so that there are no more tensions that prevent Kisar's peaceful functioning within the Indonesian republic. Influence of East-Timorese designBecause Kisar lies on the extremity of the Dutch and Portugues sphere of colonial activity, European influence on textile design is negligeable, though there is some, very slight influence of the patola that the Dutch brought in, seen almost exclusively in borders with tumpal endings. For the same reason, there are very few Kisar cloths in western collections.Ikat motifs used to be powerful indicators of status, especially on women's attire. The range of rimanu motifs, which include human figures with raised hands, rendered with adorable naiveté, double eagles, jungle fowl, ayam hutan, and eight-pointed stars was strictly reserved for the aristocracy. According to legend, any weaver who broke this taboo and 'stole' a motif not belonging to her class might be put to death. One of the main weaving centres, Fataluku speaking Oirata, the source of much of the highest quality ikat, is populated by people who originally came from the Gauteng area in Eastern Timor. When we look at the patterns from these two regions, the similarity, as Khan-Majlis already noted in her Woven Messages, is unmistakable. See for instance: Comparison 1 and Comparison 2. Clearly though, figuration developed far further on Kisar than it did on East Timor, where there is never more than a hint of figuration. What the two regions have in common, something that becomes apparent more quickly when handling the cloths then when just judging images, is a certain gentlenes. Both Los Palos and Kisar cloths exude a noteable human warmth, no doubt part of the reason why we are so attracted to them. Traditions survive, but with a harsher paletteNowadays, women still weave ikat sarongs with the traditional patterns, though with a less strict adherence to the adat which reserves certain patterns exclusively for certain clans or people of noble standing. The patterning also tends to get less elaborate. An additional, much greater, loss is that the traditional methods of dyeing with natural dyes are all but forgotten. For Kisar women of the better classes traditional ikat dress is still de rigueur for formal occasions, such as going to church, but the colours these days are quite harsh. The reds especially can be so bright as to pose a danger to eyesight. So Kisar offers the same paradox that we see in most of Indonesia: as traditions fade, their rudiments are expressed more boldly. | ||||||||||