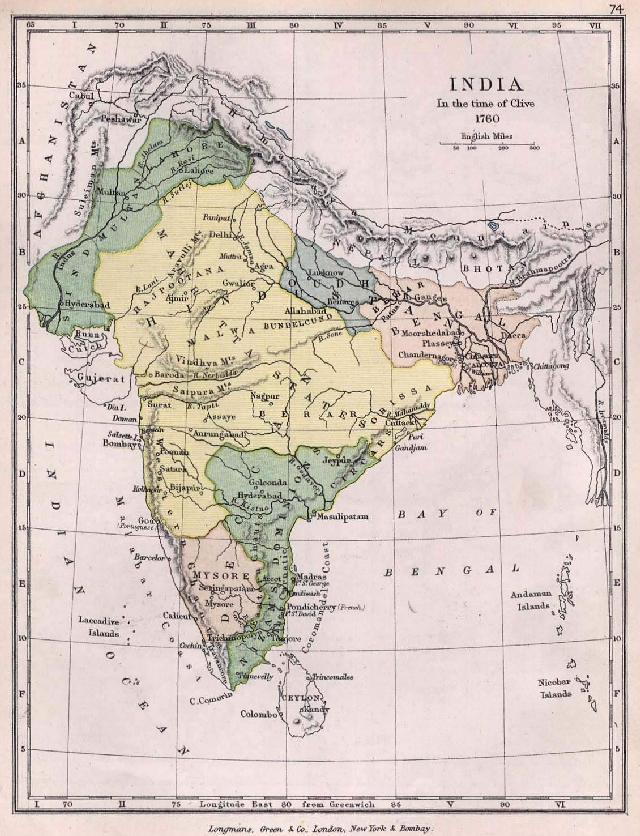

The patola from India - a foreign source of inspirationPatola, double ikat silk textiles from the Patan region in Gujarat, India, are arguably the most beautiful and accomplished of all pre-industrial textiles. Actually, patola is the plural, the singular is patolu. As the word patola is used almost universally to refer to a these cloths in the singular, and patolas to refer to a number of them, it may seem almost pedantic to use patolu instead. Still we prefer to stick with the correct wording, following the practice of most authoritative sources. The patola textiles in this collection constitute both an anomaly, and, arguably, the very heart of it. They are an anomaly because they come from India, not Indonesia - and they are central to it because they have influenced the design of Indonesian textiles, particularly ikat cloths, to a high degree. From the 17th C. onward patola from Gujarat in Western India were widely, though thinly, distributed in Indonesia and became treasured heirlooms in Java and Bali, as well as on the far-flung islands of Eastern Indonesia. Though there is no supporting documentation, it seems likely that the importing of patola to the islands that would later constitute the state of Indonesia was initiated by the Portuguese, who had established fortified trading posts at Daman and Diu on the Indian coast near Gujarat in the 16th C. (that they would hang on to, along with Goa, till the mid 20th C.). Certain is, that the Dutch, who followed the Portuguese explorers and traders close on their heels, established a large trading post at Surat, near Gujarat, and started importing patola in earnest - though never in quantity. Cargo papers of the VOC, the Dutch East Indies Trading Company document purchase of these textiles and delivery of them as gifts to various rajahs and other nobles on the Indonesian islands, by whom they were held in great esteem on account of their immediate visual appeal, almost unimaginable technical sophistication, and extreme rarity. As James J. Fox notes in his contribution to Mattiebelle Gittinger's Indonesian Textiles, on a typical shipment of one thousand trading cloths from Surat to Batavia, only five would be patola. Over time, as most of the fragile silk cloths were destroyed by insects, rot, and the sundry other degradations common in a tropical climate, their rarity has greatly increased. Even fragments of patola are traded and displayed in museums, usually framed.  The pattern that launched a thousand imitations. Tokens of allianceBecause of their rarity and immediately apparent technical superiority, the patola were not just commercial fungibles in the sense that beads and axes were in Africa, but carried the weight of tokens of alliance. As Mattiebelle Gittinger explains in Splendid Symbols, "In an effort to monopolize trade in this region, the Dutch East India Company [a.k.a. VOC] recognized and dealt exclusively with particular leaders, giving them the precious cloths as symbols of their favour. Thus the Dutch in effect created an elite, and the patola they gave in exchange for slaves, beeswax, and other products became synonymous with high social rank. When patola elements were subsequently adopted into local textile traditions, important families claimed particular design elements as their prerogative."Because patola were so admired, or even revered for the protection they were believed to afford against myriad evils, material and spiritual, their patterns inspired village weavers in Sumatra, Bali, Flores, Sumba, Savu, Roti and other islands, and were often blended with or integrated in traditional tribal textile motifs. Patola with the circular floral motif shown above were particularly treasured, as evidenced by the widespread adoption of the pattern throughout the Indonesian archipelago, by many different ethnic groups, most of which attributed patola with supernatural powers, particularly in the realm of protection. After the VOC went bankrupt in 1799, due to its owners greed and shortsightedness, and much aided by its officials' corruption, and the influx of patola was reduced to a mere trickle and imitation accelerated. Towards the end of the colonial period many weavers who were incorporating patola-inspired motifs into their work had never seen a real one. Protection against evil, material and spiritualIndonesians are not alone in attributing magical powers to objects of such technical refinement that they appear almost supernatural - the more so when their provenance is foreign and their manner of manufacture unknown. As Robyn Maxwell and Mattiebelle Gittinger write in Textiles of Southeast Asia:

On some islands the notion of protection offered by patola cloths has taken such extreme forms that the cohesion and the very existence of a clan may be said to depend on them. A powerful example of this is given by Rodemeier in her work on Pantar and Alor. More about this on the respective pages, but to briefly illustrate the point: when a certain clan on Alor ran out of patola to use as shrouds for the burial of their kings, they started cutting them up and using one meter sections, until they ran out of patola altogether. When the last fragment was used for a burial in 1999, the power inherent in the clan's ownership of patola vanished, which meant the end of the dynasty. Jilamprang and tumpalThe most important design elements borrowed from the Indian model are the jilamprang, which is often described as an eight-rayed flower but in Gujarat is known as chhabdi bhat or basket pattern, and the tumpal borders that consist of either a row of tall triangles or a row of triangles alternated with inverted triangles. Patola motifs are found on cloths all across the archipelago, from Sumatra in the West to the most remote islands in the Moluccas. Only a few islands, such as Sulawesi and Borneo show no such influence, or so little as to be insignificant; on others, such as Sumatra and Roti, the influence on certain individual textiles is so strong that one can speak of undisguised copying. Here for instance is a comparison of a jilamprang patterned patolu and a cloth from the Lio district on Flores: Patolu and Lio. And a comparison of the same patolu with a man's cloth from Roti: Patolu and Roti. (Links open in new windows.)Though such fortunate occasions are getting rarer as time progresses, now and then new types of patola are still being discovered. And as collector and dealer Susi Johnston says: "Whenever a distinctive patola turns up, it is avidly inspected by collectors and scholars to ascertain whether the pattern may have been a precursor or inspiration for specific patterns of Indonesian textiles. So every patola that we have a chance to study and appreciate, may represent a meaningful piece of the jigsaw puzzle which helps us to better understand geringsing, cepuk, and many other textile traditions in Indonesia."

Revered across the isles, but perhaps too daunting to imitate. Something of valueWithout doubt the most spectacular patola are those showing a parade of caparisoned elephants, camel riders, armed horse riders and carriages, standard bearers, fanners, lions, peacocks, and sundry other elements of power and luxury. However, they have hardly served as a source of inspiration to Indonesian weavers - perhaps because they were so awed by the complexity of these cloths that to even begin thinking of copying them left them disheartened. We do occasionally see elements of these patola appearing, e.g. on Sumba and in the Ngada region of Flores, but then of course in the simpler form of cotton weft ikat.When Alfred Bühler and Eberhard Fischer, published their standard work The Patola of Gujarat in 1979, only six of these majestic 'elephant patola' were known. A few more have since been discovered, but the total world-wide probably does not exceed ten. Our patola were acquired from impoverished local rajahs on small islands in Eastern Nusa Tenggara, after long negotiations that in the case of the elephant stretched over three days.

As collectors of ancient pieces of art (especially very old or very fragile ones) we may see ourselves as owners, proud owners perhaps, but in fact we are just their temporary guardians, whose job it to pass them on to a next generation, and who are rewarded for their effort by living in the presence of these inspiring manifestations of man's striving to create something sublime that lifts our spirit above the mundane demands of life on earth. A very limited number of elephant patola in slightly different versions, are found in public and private collections including:

| ||||||||||